A very exciting thing happened to me yesterday – I found out I’m from Africa. I know what you all are thinking…

It all started like any other semester in graduate school. I was interning in the lab of Dr. Todd Disotell at NYU, collecting some DNA, pipetting a few things – the usual. On the first day the other interns and I took our own saliva and blood to extract DNA. Our target was to amplify the HVR1 (hyper-variable region 1), a segment of our mitochondrial genome (mtDNA). Over the course of the semester we tirelessly pipetted DNA, enzymes, buffers, and dyes as we conducted PCR (polymerase chain reactions), ExoSAP procedures to clean the amplified DNA, cycle sequencing, and ethanol precipitation to finally obtain our own mtDNA sequences. We then compared our sequences to others published in databases using GenBank.

It all started like any other semester in graduate school. I was interning in the lab of Dr. Todd Disotell at NYU, collecting some DNA, pipetting a few things – the usual. On the first day the other interns and I took our own saliva and blood to extract DNA. Our target was to amplify the HVR1 (hyper-variable region 1), a segment of our mitochondrial genome (mtDNA). Over the course of the semester we tirelessly pipetted DNA, enzymes, buffers, and dyes as we conducted PCR (polymerase chain reactions), ExoSAP procedures to clean the amplified DNA, cycle sequencing, and ethanol precipitation to finally obtain our own mtDNA sequences. We then compared our sequences to others published in databases using GenBank.

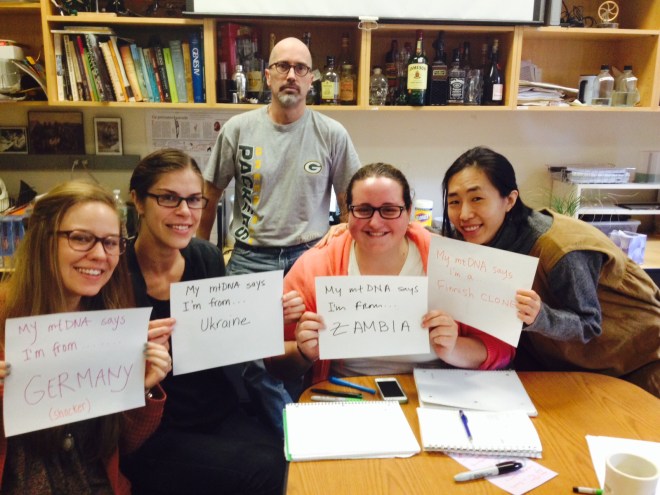

The other three interns had unsurprising results: Petersdorf aligned with individuals from Germany, Bryer with individuals from Poland and Ukraine, and Lee with individuals from China. I, however, had the first 100 matches with individuals from either Zambia, Botswana, or Namibia.

But in reality this is not so surprising, nor an accurate representation of my (or any of our) ancestry. DNA, and specifically the mitochondrial sequence, has been used for decades to assess an individual’s ancestry. This is commonly done by looking at the mtDNA of a wide sample of modern humans and segmenting out different patterns as representing more closely related groups of individuals – haplotypes.

Haplotypes, or haplogroups, are incredibly variable across modern human populations. When results show that an individual is from a particular country, what is really being reported is that that person’s haplotype is most frequently found in individuals from that country/region. It is all a statistics game. You can find more information about the different mtDNA haplogroups and their frequencies in different countries here.

So what really happened in my results was that one region (~200 base pairs long) of my mtDNA happened to resemble individuals from southern Africa. Comparing this small segment of mtDNA to my entire mtDNA and nuclear DNA sequence from National Geographic’s Genographic Project I participated in a few months ago, the results are similar, though the increased data helps provide more resolution and accuracy to my ancestry. My mtDNA haplogroup is L3E2B, predominately found in Africa with some frequencies in the Middle East and southern Europe, particularly Spain. My nuclear DNA data suggests I have recent regional ancestry in the Mediterranean, Northern Europe, Southwest Asia, and even some Native American.

Long story short, modern human populations are more similar than our outward appearances or even scientific discourse would lead us to believe. Our ancestors moved around much more than we give them credit for. Further, seemingly distant populations share more than we think they do. When archaeological or forensic analyses indicate an individual was from a particular place, that is really just reflecting the statistically safest assessment. But broader than that, understanding how much variation and geographic dispersal is present in our species should really highlight how incredibly similar we all are. Social constructs of race, and even scientific assertions of the ability to classify an individual to a group based on DNA or other physical features, cloud this reality in popular culture. We all have an inherit interest in our own origins. Simple genetic analyses can be fun, surprising, and informative. However, reported results from projects such as these should not be taken as absolute. Different parts of our genomes tell us different stories about our ancestors; the more data available the more resolution we have.

One thought on “OMG, Karen, you can’t just ask people why they’re white!”